26 November 2019

In 2008 (yes, 11 years ago!), when we shot the first footage for the Chasing Portraits documentary film, I thought I knew all the central characters to the story: my great-grandfather’s paintings, Dad, the museums and private collectors who had my great-grandfather’s paintings in their possession, and me. What I didn’t know then was that during post-production editing I would discover another character: my boots. I wrote a slightly tongue-in-cheek essay about the boots to celebrate today’s release of the film on DVD and Video on Demand (VOD). I know I’m not alone in seeing the boots as a character; just recently a student at the SFSU screening of the film asked me about them (and he’s not the only one to have done so). If you haven’t had a chance to catch the film at a festival, I hope you watch the it before you read the essay [Buy Chasing Portraits from First Run Features, Amazon, iTunes, Best Buy, Walmart, Barnes&Noble, or watch it on Kanopy]

NOTE: All photos are stills from the Chasing Portraits documentary film and are the work of my Director of Photography, Sławomir Grünberg.

Boots

I wear a lot of hats; mostly of the metaphorical variety. On some level, I suppose we all do. I put on my writer hat when I sit down at the computer, waiting for inspiration to fill the blank screen. Now that I’m a published author, it’s clear that I’ve tossed my hat into the creative ring, which signals to others that it’s fair game to critique my writing. Speaking of games, I don’t have any hat tricks to my name – I never was very good at sports, but at the drop of a hat I am ready to go for a walk, where I often find my muse. Of course, I like to tip my hat to those whose accomplishments inspire me. Over the last decade I’ve put my hat in hand and then passed it around, seeking donations for my documentary film. I’m never far from wearing my mom hat, trying to keep my boys on track to wear their own variety of hats someday. But lately I’ve been wearing another sort of hat, my thinking hat, to ponder the meaning of shoes.

Wearing the right shoe makes all the difference in someone’s ability to do their job successfully. A ballerina needs pointe shoes, ice hockey requires skates, soccer players wear cleats. Authors depend on shoes too. I like to write while wearing fuzzy slippers. I prefer flats for giving talks. But more to the point, or to stretch the metaphor, perhaps more to the pointe, authors also depend on shoes to better describe characters. Mother Goose famously rhapsodized about an old woman who lived in a shoe. Frank Baum gave Dorothy ruby red slippers to click three times to journey home from Oz. Puss wore a pair of boots while he tricked the King into giving his daughter’s hand in marriage to Puss’ poor master. Cinderella lost her glass slipper at the ball, which ultimately led to her reunion with the prince.

Shoes are featured prominently in many fairy tales and young adult fiction, but shoes are also often important in the books adults read. They say to never judge a book by its cover, but the cover of Cheryl Strayed’s book, Wild, features the photograph of a single boot, and as much as I hate to put on my contrarian hat, it seems a fine way to judge her story. The hiking boot represents both the actual boot Strayed lost over a cliff while hiking the Pacific Crest Trail as well as the soul-searching inner journey she made in an attempt to make sense of her life. Before Sex and the City was an HBO show and a movie, it was a series of books by Candace Bushnell who wrote about her social adventures, romance, and spike heeled Manolos. Carrie Bradshaw, played by Sarah Jessica Parker, says lots of things about shoes in the HBO series. In a not so subtle nod back to Mother Goose, she famously said, “I’ve spent $40,000 on shoes and I have no place to live? I will literally be the old woman who lived in her shoes!” And Arthur Conan Doyle often provided Sherlock Holmes’ suspects with distinctive shoes, and footprints, so that he might better assess a suspect’s gait, social class, and working profession.

I’m not exactly obsessed with shoes, but I have at least my fair share (I own twenty pairs which doesn’t seem like an excessive number, but it’s clearly a lot of shoes. By comparison, Imelda Marcos reportedly owned one thousand sixty). There is one pair of shoes in my closet that keeps poking at me to think about and write about. It inspires me to dust off and put on my academic hat (After my master’s degree, I did one year of a PhD program in Pennsylvania). It’s a pair that I didn’t notice at the time, but which has a recurring, accidental presence in both my memoir and documentary film.

The shoes in question are actually a pair of boots. They’re black, clunky heel Clarks that zip up on the inside of my calf to just below the knee. They sport a decorative buckle whose only job is to look shiny. I’m not sure when, or where, they were purchased. I do know that they first appeared in my own writing in early 2014 when I wrote about a trip to Toronto, Canada, where I made an important discovery about an archive at the University of Toronto. I wrote of my journey to the library, “It was raining. I was wearing a cotton Lands’ End wraparound dress and chunky-heeled black leather boots, and as we stepped out onto the street a bit after 6 p.m., I realized it was freezing cold.”

The shoes in question are actually a pair of boots. They’re black, clunky heel Clarks that zip up on the inside of my calf to just below the knee. They sport a decorative buckle whose only job is to look shiny. I’m not sure when, or where, they were purchased. I do know that they first appeared in my own writing in early 2014 when I wrote about a trip to Toronto, Canada, where I made an important discovery about an archive at the University of Toronto. I wrote of my journey to the library, “It was raining. I was wearing a cotton Lands’ End wraparound dress and chunky-heeled black leather boots, and as we stepped out onto the street a bit after 6 p.m., I realized it was freezing cold.”

Some authors struggle with whether or not to put themselves into their writing. In early drafts of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Rebecca Skloot reportedly worked hard to keep herself out of the book’s narrative. But she did write herself into the book and did so while simultaneously writing about shoes which she spied while visiting the home where Lacks grew up. Skloot wrote, “Upstairs, in the room Henrietta once shared with Day, a few remnants of life lay scattered on the floor: a tattered work boot with metal eyes but no laces, a TruAde soda bottle with a white and red label, a tiny woman’s dress shoe with open toes. I wondered if it was Henrietta’s.” Skloot knew the story wasn’t hers, it belonged to the Lacks family. But she was so invested in its details that writing about herself as a young journalist helped make an incredibly compelling narrative.

Clearly authors take liberties in how they portray themselves in their work, but they also have total control over how much and what they share of themselves. In contrast, a documentary film subject, even when they are the Producer and Director like me, doesn’t have full control over a cinematographer’s creative instincts.

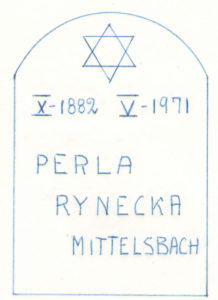

In 2014, I travelled to Poland to film footage for my documentary, CHASING PORTRAITS; a film about my Jewish great-grandfather, Moshe Rynecki (1881-1943), who perished in the Holocaust, and my quest for his lost paintings. Sławomir Grünberg, my Director of Photography, was responsible for filming interviews, street scenes, and visits to antiquity markets as I searched for clues to my great-grandfather’s past. I didn’t watch too much of the footage as we filmed it over a period of several weeks, but two years later when we began film editing, I realized he’d filmed my boots quite a bit.

While I made a conscious decision to include the boots in my book, I had no idea how often Sławomir would film them during our time in Poland. I certainly never told him to film them, or to take broad shots that would show them. And yet, there they were, again, and again, and again — standing on a train platform, sitting on a park bench, walking along the Vistula River. They are ubiquitous in the footage from Poland — Sławomir seemed to find them enchanting. There is, however, a big difference between the appearance of the boots in one sentence in my book to help set the scene and realizing that somewhere along the line my boots took on a life of their own. And honestly, I’m not sure if the boots took on a life of their own, or if it was Sławomir who, like Geppetto in Pinocchio, brought them to life.

Shoes aren’t always so captivating, but they tend to say something about the person who wears them. Like Sherlock Holmes, I like to examine shoes for what they can tell us about people we don’t know. At Majdanek, the Nazi concentration and extermination camp where we believe my great-grandfather was murdered, there is a seemingly endless display of shoes worn by camp prisoners (and its victims). On the top of the pile it’s possible to see a small child’s shoe, a man’s worn leather loafer, and a boot with missing laces. These shoes speak silently of those whose lives ended so suddenly and so tragically.

I’ve never been to see The Shoes on the Danube Bank, a memorial in Budapest, Hungary. Conceived of by film director Can Togay, and designed by sculptor Gyula Pauer, it seeks memorialize those who were ordered to stand at the river’s edge and take off their shoes, so that when they were shot their bodies would fall into, and be carried downstream, by the river Perhaps film directors know a thing or two about the powerful image of shoes.

I’ve gotten used to seeing my boots over and over again in the Polish footage from CHASING PORTRAITS. While at first I laughed at their ubiquity, now I look for them in the film, and wear them at home for good luck. They are comfortable old friends. I have walked many hundreds of miles in those boots over the course of my decades long project. I like to think I am resilient and persistent in the face of obstacles in my project, as in life. And like my resilience, sometimes the endless stream of obstacles and sheer number of miles scuff my boots up and wear them down over time. Perhaps that’s why I recently had them re-soled, both to ensure their longevity but also to reinvigorate my own soul — to keep me walking down those miles and moving past those obstacles.

I’ve gotten used to seeing my boots over and over again in the Polish footage from CHASING PORTRAITS. While at first I laughed at their ubiquity, now I look for them in the film, and wear them at home for good luck. They are comfortable old friends. I have walked many hundreds of miles in those boots over the course of my decades long project. I like to think I am resilient and persistent in the face of obstacles in my project, as in life. And like my resilience, sometimes the endless stream of obstacles and sheer number of miles scuff my boots up and wear them down over time. Perhaps that’s why I recently had them re-soled, both to ensure their longevity but also to reinvigorate my own soul — to keep me walking down those miles and moving past those obstacles.

be surprised by either of these experiences. With both the publication of my book, and the release of the film, I’ve discovered that people share their opinions with me on pretty much anything.

be surprised by either of these experiences. With both the publication of my book, and the release of the film, I’ve discovered that people share their opinions with me on pretty much anything. While I’m troubled by these first two questions, it’s a third that I’ve been asked multiple times that particularly bothers me: Which is fundamentally better, Chasing Portraits the book or the film? I am not entirely certain how I am expected to answer this question. I am, after all, the Producer/Director/Protagonist of the film and the Author of the book, and I am proud of both. Books and documentary films are different art forms, and you can do different things with the written word than you can do on film, and vice versa, so my best answer is that that they’re companion pieces. My needs and experiences are different than that of an audience seeing or reading Chasing Portraits for the first time. The question I want to answer here is not so much which is inherently better, but which is better for me. The answer is complicated.

While I’m troubled by these first two questions, it’s a third that I’ve been asked multiple times that particularly bothers me: Which is fundamentally better, Chasing Portraits the book or the film? I am not entirely certain how I am expected to answer this question. I am, after all, the Producer/Director/Protagonist of the film and the Author of the book, and I am proud of both. Books and documentary films are different art forms, and you can do different things with the written word than you can do on film, and vice versa, so my best answer is that that they’re companion pieces. My needs and experiences are different than that of an audience seeing or reading Chasing Portraits for the first time. The question I want to answer here is not so much which is inherently better, but which is better for me. The answer is complicated.

I really should have written these a long time ago. Hopefully it’s better late than never! Is your book club reading

I really should have written these a long time ago. Hopefully it’s better late than never! Is your book club reading