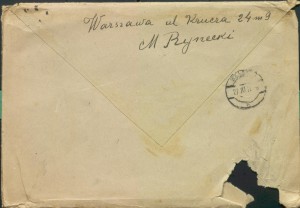

In 1970 a young Polish boy and his recently divorced father moved from Poland to Denmark. Later, the boy’s mother remarried. The man she married, Edward Rajber, was (for many years) the Chairman of the Socio-Cultural Association of Jews in Poland (TSKŻ), a secular Jewish organization founded in 1950 with the merger of the Central Committee of Jews in Poland and the Jewish Cultural Society. In 1975, Chairman Rajber was given a gift to thank him for his service to the organization. That gift? A Moshe Rynecki painting.

In 1978, the boy’s mother, Hanna Mistowski, remarried. In 1984 when Edward Rajber died, his widow inherited the painting.

In December 2021 Hanna passed away and her son began sorting through his mother’s belongings which included the Moshe Rynecki painting.

At first the Polish-Danish man wanted to sell us the painting. Then he decided not to sell the painting. Then I sent him a copy of my book, Chasing Portraits. Many months passed and eventually I received an email, “This painting should belong to you.”

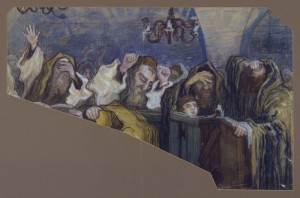

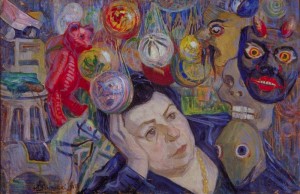

We wired funds to package and ship the painting to California. It arrived in October 2023. The frame was broken and the glass had cracked, but the painting was in good condition.

Painted in 1929 by Moshe Rynecki (1881-1943). Now back in our family. Kind of gives me goosebumps.

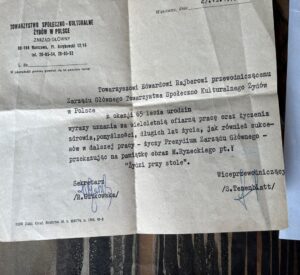

[Translation of the Polish documentation: Comrade Ed Rajber, Chairman of the Board of the Main Cultural Society of Jews in Poland, on the occasion of the 65th birthday, in appreciation for many years of dedicated work and wishes health, prosperity, long years of life, as well as success in further work – wishes the Presidium of the Main Board – by handing over the painting by M. Rynecki: Jews at the table vice-chairman,/S. Tenenblatt Secretary,/R. Gutkowska]

NOTE: I do not know how the TSKŻ obtained my great-grandfather’s painting.

The shoes in question are actually a pair of boots. They’re black, clunky heel Clarks that zip up on the inside of my calf to just below the knee. They sport a decorative buckle whose only job is to look shiny. I’m not sure when, or where, they were purchased. I do know that they first appeared in my own writing in early 2014 when I wrote about a trip to Toronto, Canada, where I made an important discovery about an archive at the University of Toronto. I wrote of my journey to the library, “It was raining. I was wearing a cotton Lands’ End wraparound dress and chunky-heeled black leather boots, and as we stepped out onto the street a bit after 6 p.m., I realized it was freezing cold.”

The shoes in question are actually a pair of boots. They’re black, clunky heel Clarks that zip up on the inside of my calf to just below the knee. They sport a decorative buckle whose only job is to look shiny. I’m not sure when, or where, they were purchased. I do know that they first appeared in my own writing in early 2014 when I wrote about a trip to Toronto, Canada, where I made an important discovery about an archive at the University of Toronto. I wrote of my journey to the library, “It was raining. I was wearing a cotton Lands’ End wraparound dress and chunky-heeled black leather boots, and as we stepped out onto the street a bit after 6 p.m., I realized it was freezing cold.”

I’ve gotten used to seeing my boots over and over again in the Polish footage from CHASING PORTRAITS. While at first I laughed at their ubiquity, now I look for them in the film, and wear them at home for good luck. They are comfortable old friends. I have walked many hundreds of miles in those boots over the course of my decades long project. I like to think I am resilient and persistent in the face of obstacles in my project, as in life. And like my resilience, sometimes the endless stream of obstacles and sheer number of miles scuff my boots up and wear them down over time. Perhaps that’s why I recently had them re-soled, both to ensure their longevity but also to reinvigorate my own soul — to keep me walking down those miles and moving past those obstacles.

I’ve gotten used to seeing my boots over and over again in the Polish footage from CHASING PORTRAITS. While at first I laughed at their ubiquity, now I look for them in the film, and wear them at home for good luck. They are comfortable old friends. I have walked many hundreds of miles in those boots over the course of my decades long project. I like to think I am resilient and persistent in the face of obstacles in my project, as in life. And like my resilience, sometimes the endless stream of obstacles and sheer number of miles scuff my boots up and wear them down over time. Perhaps that’s why I recently had them re-soled, both to ensure their longevity but also to reinvigorate my own soul — to keep me walking down those miles and moving past those obstacles.