“You’re brave,” she says.

She’s not someone I know. She’s just seen Chasing Portraits and waited in line for several minutes so she might have a private moment with me. I nod and say, “thank you.” I’m careful to be sincere and modest, but I DO feel brave for sharing my story, aware that film reviews will soon come out and that not everyone will love my movie.

“I could never have allowed myself to be filmed without makeup,” she says.

Wait, what? I’m stunned. While it’s true that in most of the film I don’t wear any makeup (there’s one scene where I sport a bit of rouge and lipstick) I can’t help but wonder how, of all the things she might want to tell me (that my great-grandfather’s art is beautiful or that she feels inspired to document her family’s history), she has instead chosen to speak with me about my personal decision to not wear makeup. That I wear none, and that this is what she will always remember about my film, is one of the lowest points of my filmmaking experience.

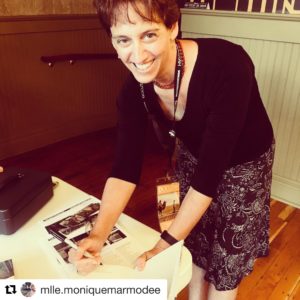

Sadly, commentary on my decision to be makeup free is not the strangest thing said to me after a showing. A college student once arrived 30 minutes late to a screening and then later asked if I could please tell her what she missed. I looked at her, at the floor, at the movie flyers in my hand and then said the only thing that I could: “You’ll just have to find a way to watch it at another time. It’s too hard to summarize.” She seemed not at all embarrassed by her question but disappointed by my response. I suppose I shouldn’t  be surprised by either of these experiences. With both the publication of my book, and the release of the film, I’ve discovered that people share their opinions with me on pretty much anything.

be surprised by either of these experiences. With both the publication of my book, and the release of the film, I’ve discovered that people share their opinions with me on pretty much anything.

While I’m troubled by these first two questions, it’s a third that I’ve been asked multiple times that particularly bothers me: Which is fundamentally better, Chasing Portraits the book or the film? I am not entirely certain how I am expected to answer this question. I am, after all, the Producer/Director/Protagonist of the film and the Author of the book, and I am proud of both. Books and documentary films are different art forms, and you can do different things with the written word than you can do on film, and vice versa, so my best answer is that that they’re companion pieces. My needs and experiences are different than that of an audience seeing or reading Chasing Portraits for the first time. The question I want to answer here is not so much which is inherently better, but which is better for me. The answer is complicated.

While I’m troubled by these first two questions, it’s a third that I’ve been asked multiple times that particularly bothers me: Which is fundamentally better, Chasing Portraits the book or the film? I am not entirely certain how I am expected to answer this question. I am, after all, the Producer/Director/Protagonist of the film and the Author of the book, and I am proud of both. Books and documentary films are different art forms, and you can do different things with the written word than you can do on film, and vice versa, so my best answer is that that they’re companion pieces. My needs and experiences are different than that of an audience seeing or reading Chasing Portraits for the first time. The question I want to answer here is not so much which is inherently better, but which is better for me. The answer is complicated.

Reaching Audiences

As a reader I love book events! What’s not to love about meeting your writing heroes?! As an author I can confirm that chatting with readers eager to purchase your book and have you sign it is pretty darn phenomenal. But if I look at my ability to reach audiences, given the sheer number of festivals the film has played in across Poland, Israel, Canada, and the United States, and the size of those audiences, it’s safe to say that far more people have seen my documentary than have purchased the book. By that measurement, I love the film more. Besides, nothing quite beats a sold-out film screening and I’ll never forget standing on the Lincoln Center stage in New York and seeing 300 people waiting for the house lights to dim and the film to begin. The reality, however, is that Chasing Portraits has had a limited number of screening engagements and is not yet available as a video on demand. While I hope more venues screen the documentary, and that more people can eventually access it on their own time, it’s probably far easier for people to get their hands on a copy of the book.

The Medium and the Message

Film Still. Photographer: Slawomir Grunberg

I’m incredibly fortunate to have both written the book and made the documentary film. The opportunity to come at the experience from two slightly different angles is unique. In the process I’ve learned quite a bit about how different art forms influence the way a story is told and remembered.

As an author I’m grateful for the way my story unfolds over the course of 23 chapters and almost 400 pages. There’s a lot of detail and nuance in the book that allows readers to really dive into the backstory, legal issues, and archives central to the Chasing Portraits story. From that perspective, it feels like film audiences ought to be required to read the book before they come to the film; by doing a smidge of homework they might enjoy the filmic experience that much more.

Film Still. Cinematographer: S. Leo Chiang

On the other hand, the film captures my relationship with my father in a way I never imagined before we began the film editing process. The best example of this is the film’s opening scene. Dad and I are on a road trip, engaged in a serious conversation about the Holocaust and my reluctance to visit Poland, but then Dad puts the camera down, forgets to turn it off, and starts talking about his delicious cup of coffee. The juxtaposition of the lighthearted moment with Dad’s reticence to talk about the Holocaust signals several things to audiences: that the film documents a physical and emotional journey, that father-daughter relationships are complex, and that although topics in the film might not always be comfortable for the subjects or the viewer, it’s okay to laugh because in life, funny things and serious things often happen together.

The power of film is, in part, its ability to marry together images, music, and dialogue in a way that envelops viewers into the heart of the story. This moment does that all in a way that I don’t think I could have ever successfully pulled off in the book. There’s something about how it’s a very private moment playing out in a very public way that gives it more power than it ever would have had on the printed page.

Narration

Book narration has similarities to a film’s voice over, but they’re definitely different creatures. Obviously, an author controls the written page and a filmmaker controls what’s on the screen, but there’s only so much you can control in terms of how subjects answer questions and how other random factors play themselves out on screen. The scene that best demonstrates these differences is my visit to Majdanek, the Nazi concentration camp. In the book readers get inside my head where they hear my trepidation about visiting the place where my great-grandfather perished. In the film I say nothing during my time at Majdanek. There is no dialogue nor is there any voice over. The film relies on the cinematographer’s ability to capture my mood in his framing choices and the sound ambiance (it was incredibly rainy and windy that day) which plays an enormous role in conveying my distress. But the other factor is that I’m not an actress (which is good because people know everything they see me do comes from an honest place) which means I don’t quite know how use my body language to convey the words that come so easily to me on the printed page: miserable, plodding, numb, helpless. I am certain that readers and film audiences experience the Majdanek a bit differently, but ultimately, both convey my distress at visiting the camp.

Experiencing the Art

Photo by Chuck Fishman

The Chasing Portraits story is a visual one. It is, after all, about my great-grandfather’s paintings. This is why there is a color insert of the art in the book and a great deal of my great-grandfather’s paintings appear at different junctures throughout the film. While the photos in the book provide an important way for readers to connect with the images, there’s something majestic about seeing the paintings projected on a big screen in a dark theater. The larger than life images and their vivid colors often makes seeing the paintings so visceral for audiences that they sometimes audibly gasp. I like that the photos in the book give readers time to linger over the images, but I am enamored with how beautiful the paintings look in the film.

And so, if you’re asking me which is better, the book or the movie… I think you should read the book and then go to the movie. But do it quickly before we write the musical, because then you’ll really have a backlog on your to-be-read and watched pile.

First-time filmmaker Elizabeth Rynecki is the great-granddaughter of Polish-Jewish artist Moshe Rynecki (1881-1943). Her book, Chasing Portraits: A Great-Granddaughter’s Quest for her Lost Art Legacy, was published by Penguin Random House in 2016. Her film, Chasing Portraits, is distributed by First Run Features. Learn more at https://www.firstrunfeatures.com/chasingportraits.html