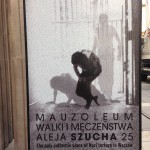

I visited Majdanek on Thursday (23 October 2014) to pay respects to what is believed to be the site of my great-grandfather’s death. It rained all day and the wind was cold and bone chilling. I won’t write much here because the visit was emotionally powerful and I’m still trying to understand what I saw and experienced. I’m including a few photographs as well as an excerpt from my grandpa George’s book that talks about why my family believes Moshe Rynecki perished at Majdanek.

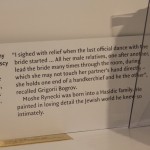

“The fact that my father died in Majdanek came to our knowledge in this manner. When the Germans started to make so called Jewish resettlements, they were afraid of resistance. They (the Germans) knew, of course, what kind of resettlements they were talking about. Death camps and crematoria. In the beginning, once they would fill up a camp, let’s say Treblinka, they would try and succeed to quiet down the Jews by giving them a bit more food for a few days and encourage them to write to families or friends that everything is well and that they have good food and peace. The Germans would declare that anyone writing a “good” letter would be immediately given work and better conditions to live. The Jews invariably would fall for it. They would write letters or cards and wait in queue to deliver them. The Germans would pick up the writings and send the writers to the gas chambers at once. The cruelty of it is of enormous dimensions. As a fact, the ones who wouldn’t write would have been sent back to the barracks to do it, and come back to get what they have been promised. Whole towns were deceived this way. This is how my father’s card came to Warsaw to my mother’s address, and made many people believe that he was well, and that he was actually painting in the camp. We know now that the minute he delivered his letter, he was killed by gas. Deception made the Jews be peaceful and believing in German lies.

For some reason or another, I never believed the Germans. This is probably why I am still alive.

Where Hitler found all these diabolic people to execute at his will, none will ever know. The Germans, and I am talking about 95 percent of them, were proud of their Fuhrer, and how smart he was. He committed genocide on the Jewish, Polish, Russian people, and nobody knew about it until it actually was too late, and even then in 1943 nobody did a thing for the poor condemned. Here Hitler knew that no country would help. The Jews were alone. So were the Poles. The Russians didn’t care. They are not much off the barbarian German character anyway. The world was with Hitler, but the strategies of Churchill, Roosevelt were wrong and too late. Some day history will prove the West was wrong from 1939 on.” Surviving Hitler in Poland: One Jew’s Story by George (Jerzy) Rynecki

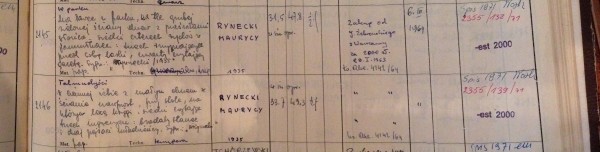

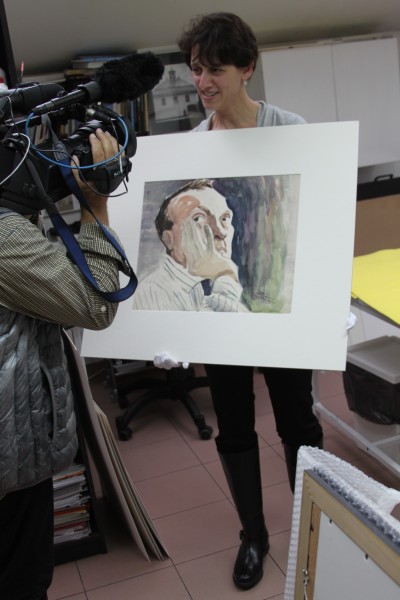

For the last 9 days, we have been visiting many sites in Poland that each play some part in piecing together the puzzle of Moshe Rynecki’s life and work. We have relied upon the

For the last 9 days, we have been visiting many sites in Poland that each play some part in piecing together the puzzle of Moshe Rynecki’s life and work. We have relied upon the

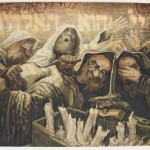

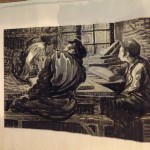

sculpture from the holdings of the Jewish Historical Institute.

sculpture from the holdings of the Jewish Historical Institute.