I love travelling to new cities because I like to explore the streets, see the museums, check out the restaurants, people watch, and to get to know the “vibe,” (if you will) of each different place. I have never visited a city where the primary goal for my visit is to uncover the traces of my family’s history. Visiting Warsaw is both fabulous and incredibly eerie for me. I am taking in the sites – and there are so many of them since I’ve never been to Poland – but I am constantly overwhelmed and haunted by the reminder of all that was lost in the Second World War.

Yesterday (18 October 2014) the Chasing Portraits documentary film crew team (myself, Catherine Greenblatt, and Slawomir Grunberg) took in over 10 locations mentioned in my grandpa George’s memoir that hold significance to my family. These locations, spread throughout the city meant that we walked, a lot, took cabs, and rode the street car to get to the various locations. At each site we then spent time filming…shots of me looking at the site, exploring the location, walking up to the site, walking away from the site…. it’s all a lot of work to get all the possible footage that we need for various scenes in the film. I hope that someday you get to see portions of all of the footage. In the meantime, here are some behind the scenes shots with a brief description of why we were in these locations.

Zacheta (the building behind me in the selfie) and Saski park.

The Zachęta National Gallery of Art (Polish: Narodowa Galeria Sztuki), is one of Poland’s most notable institutions for contemporary art. The translation of the word zachęta is something like, encouragement or motivation, and refers to the Towarzystwo Zachęty do Sztuk Pięknych, the Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts founded in Warsaw in 1860. Moshe’s work was shown here, across the street from Saski Park, in the interwar years on several occasions.

There’s a story in grandpa George’s memoir about having an office on Mazowiecka Street during the war. In one scene, he approaches his office and hears someone asking to see Jan Traska, the false name my grandpa used during the war. Grandpa George knew this was trouble, so he quickly went down a back stairwell, and down Mazowiecka street towards Jerozolimskie Blvd, to grab a street car going anywhere away from where there was danger. I don’t have an address for the building of the office, but we had a serendipitous moment where we discovered the remains of the walls of a pre-war building still standing on the street. Inside the courtyard is a plaque, in Polish of course, that says something about remembering the artists of Warsaw who perished in the war. In this shot at the left you can see Slawomir filming me reading the plaque. I’d love for someone to write out the translation for me! [if you can do this, please email it to me: elizabeth@rynecki.org] [19 October 2014. Thank you to Piotr Nazaruk and Jan Laskowski for translating the plaque! It reads: “In memory of 400 Polish artists, Nazi victims who died fighting on all fronts of World War II or were killed in the years 1939-1945 – Association of Polish Artists, Warsaw 1968”]

Just like grandpa George, we continued down Mazowiecka Street towards Jerozolimskie Blvd and took a street car headed south.

Unlike grandpa George, we didn’t have the Gestapo chasing us, so we took a leisurely ride and then got off the train and began our walk towards Tamka 29…the place where my great aunt, Bronislawa had her dental practice. There were once many Rynecki paintings that hung in her office. Moshe told his children (George and Bronislawa) that people getting dental work needed pretty pictures to look at to distract them from all the pain in their mouths. We took a break before we got to the Tamka address at a lovely bakery (a film crew has got to eat!).

I know that searching for the addresses of buildings that once existed is a bit crazy. I’m chasing ghosts in the locations that once held meaning to my family, and it’s not like I’m actually going to be able to go in, visit, and see Rynecki paintings on the wall. But somehow, seeing this brand new building under construction with the very prominent “Tamka 29” sign (there were several of them on the fence) was a bit much for me. If you’ve ever seen the movie Grosse Point Blank where John Cusack goes to the location of his old home and discovers a convenience store, well, that’s about how I felt yesterday when I saw this building…

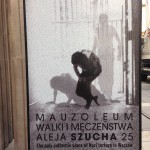

After our visit to Tamka Street we stopped in the gift store of the Chopin Museum, then walked onto Nowy Swiat (a rather swanky street in Warsaw) where we waited for a cab [here’s a photo of Cathy in the cab holding one of the camera bags!] to whisk us away to Szucha 25 (the former Warsaw Gestapo offices). It was at this office where Grandpa George went to obtain papers to travel to Gdynia. He wanted/needed to go check on his fish-import business during the war. While he stood in line a man recognized him (a local pharmacist) and whispered in his ear that he best leave immediately or face arrest. Today there is a museum in this location with the unfortunate title of Mauzoleum (I’m hoping that this means something better in Polish….)

Then it was a stroll on Ujazdowski blvd (the street where the German Nazi army paraded their victory over Warsaw), and onto Krucza 24 (the site where Moshe Rynecki had an apartment, his art studio, and an art supply store where Perla sold papers, paints, and paint brushes to artists and art students from around the city. We then met up with Alex Wertheim for an interview (see Cathy’s Corner below) and afterwards it was off to a tour of parts of the former Warsaw Ghetto and the remains of the ghetto wall.

Cathy’s POV: Warsaw is a photogenic city. It takes a little while to discern its layers: the prewar buildings that somehow survived the war (they are few but they are here), the reconstructed city that recalls in faithful detail all that was destroyed, the monumental Soviet apartment blocks that house so many Warsovians, and all of the many signs of the emerging 21st century economy that gives Poland some muscle in the EU. Poland’s history is more complex than I could have imagined six months ago, when I began to do research for this trip. Its ghosts speak on every street and corner, and they compete for attention in an already crowded airspace. What they have to say is often not simple to hear or decipher. Yesterday, we interviewed Alex Wertheim, whose family found Moshe Rynecki paintings at the end of the war. Some of the paintings are in Toronto, some are in Israel, we thought that some were here, but it doesn’t seem that they are anymore. What Alex told us somewhat differs from what his brother Moshe recounted last year. How their stories differ is something for us to reckon with as we make this film. When collecting fragments of history and personal memory, what we find does not simply align to form a seamless picture. This is what makes this all so compelling.