A CHASING PORTRAITS reader recently emailed me to ask what had happened to Perla, my great-grandmother, after she brought the bundle of Rynecki paintings from Poland to her son (my Grandpa George) in Italy. Could I, she asked, please tell the rest of Perla’s story?

This simple request struck a chord with me. I’ve always felt bad that Perla disappears from the book after she delivers the surviving bundle of art to Dad and his parents in Italy. She last appears on page 96 of CHASING PORTRAITS where it is April 1947 and Perla prepared a list of Moshe’s work for the Polish Ministry of Culture and Art. I wrote, “With permission to take the art out of Poland, Perla planned a trip to Rome.”

Perla did go to Rome. There’s a black and white photograph of Perla, Dad, and my grandmother (page 92) when she was in Italy. After her visit to Italy, she returned to Poland. I can only guess as to why she didn’t stay in Italy — she didn’t speak the language, she couldn’t find work, she missed the familiarity of Poland. The last one is a little more complex than it sounds. Clearly Perla missed Poland, but in a way she missed a Poland that for the most part had vanished. In the post-war years, Poland, and especially Warsaw, was suffering as it tried to rebuild not just physical buildings and bridges, but to reconstruct the whole fabric of a country- economic, political, and social- almost from scratch. She couldn’t really live in Warsaw itself because the city was in ruins, so for a period of time she lived in Lodz, but things there were also difficult. She relied upon CARE packages and money sent from my grandmother’s Chicago family in order to survive.

This story is very interesting to me, and in an earlier draft of the book, I wrote a chapter about Perla’s life after the war. From a narrative perspective, unfortunately, following Perla’s trajectory meant derailing the main storyline of the book, so in the interest of narrative focus I deleted it. And quite honestly, finding a good way to tell Perla’s post-war story, when I really only knew pieces of it, was a struggle. But I do know the broad outlines of Perla’s story, and given reader curiosity, now seems like a good time to share what I know.

If you’ll recall, Dad and his parents left Italy and arrived in Texas in late 1949. They first lived with extended family in Denison, and later in Dallas. After two years, Grandpa George grew antsy. He greatly appreciated all the Texas family had provided – a place to land in America, a job, and family support when there were so little of it left in the world – but he never felt like Texas was where he belonged. I don’t know exactly when he made the decision to “Go West” to California, but interestingly enough Grandma moved out first, taking a train to San Francisco and securing a job making hats. Dad and Grandpa George moved a bit later, driving to California with all their personal belongings. I assume the Rynecki paintings were in the trunk of the car, but Dad doesn’t remember. Upon arriving in California, the family briefly settled into an apartment in San Francisco. Within a couple of years, the family moved north when Grandpa George secured a job working for a scrap metal business in Eureka, California. Eventually, he saved up and bought the business.

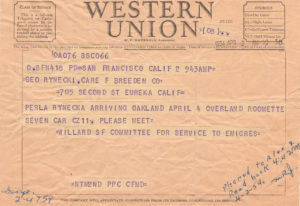

While Grandpa George worked to gain his financial footing, he also tried to sort out how to bring Perla to California. I don’t know if she wanted to leave Poland or if Grandpa George simply wanted her closer, so he could help her out. In July 1953 (about four years after Dad and his parents arrived in the United States) Grandpa George received a letter from the San Francisco Committee for Service to Emigres that his mother was entitled to consideration under section 3(c) of the Displaced Persons Act to come to the United States. In February 1954 Perla’s quota number was called and in March she left Europe aboard the SS American bound for New York City. Grandpa George hoped she would fly from New York to California, but Perla insisted on taking the train. On April 2, 1954, Perla arrived in Oakland, California, by train in, as the Western Union telegram reported, an “overland roomette.”

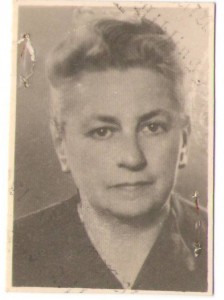

Perla was about 72 years old when she arrived in California. I wish I knew what she thought about leaving Europe, or her first impressions of America, but all I have are my educated guesses. What I can surmise is that to leave behind everything she knew, even though the war destroyed so much, must have been incredibly difficult, especially for a woman in her seventies. Although I’m not certain, it’s very unlikely that she spoke any English when she arrived, and certainly adapting to American customs must have felt like a struggle. I assume Grandpa George was excited to bring his mother to the United States, but nervous about the added financial responsibility of taking care of her. My grandmother probably had mixed feelings about her mother-in-law’s arrival as it would certainly make further demands upon her. Dad was eighteen when Perla arrived. He had been in America for five years, and while he has never told me much of anything about his relationship with his grandmother, I’m guessing that as a teenager, he didn’t devote as much time to her as she might have liked. It’s not hard to imagine that generational and cultural differences made things difficult for everyone. When pressed for memories, Dad recalls only that Perla once told him that life in Eureka was an “eat and sleep” existence. The implication was that she was bored and didn’t much like the lifestyle.

Perla eventually decided to leave California and move to France where she had family. I don’t know if there was some precipitating event: a disagreement, the shock of experiencing her first earthquake (just eight months after her arrival, there was a 6.5 earthquake centered in Eureka), or if she simply decided that life in America wasn’t for her. I also don’t know exactly when she left Eureka, but when she did go (with some Rynecki paintings), she went to live with cousins in Le Mans, France. She stayed with them until they could no longer take care of her and then she was placed in a long-term care medical facility.

Perla’s life is largely a mystery to me both because I never met her and because I never heard Grandpa George speak of her. She, on the other hand, did know about me. In September 1969, just one month after my birth, Perla wrote a letter which mentioned me. I translated only a small portion of the letter written in Polish, in part because of my unfamiliarity with Polish letter combinations, but also because her loopy handwriting is tough for me to decipher. Despite the challenges, one phrase stood out. Perla wrote: “całusy dla Elisabeth Bella,” which translates to, “kisses for Elisabeth Bella.” Perhaps it’s overly sentimental of me, but when I first translated this phrase, I cried.

That Perla was able to write a letter sending me kisses is rather remarkable when you realize she wrote the letter from a nursing home which reported her mental health as “not good.” Federation Des Societes Juives De France, the facility she lived in at the time of my birth, felt her situation had so deteriorated that they were no longer equipped to handle her medical needs. They told Grandpa George, “unfortunately, due to her mental state she needs permanent help to attend to her, which we cannot provide.”

Perla

While I like to think my birth provided Perla a ray of sunshine in a very difficult and depressing time, she was not well and her son, many thousands of miles away, fretted about her. Unfortunately, Grandpa George’s own health was not great, and he was unable to travel to France to be by her side. Instead he wrote many letters to the institutions caring for her, asking for information about her physical and mental well-being. The news was not good. About the same time that I turned one, Chateau De Villeniard, the private nursing home where she lived, wrote: “She is a person who is often very restless and with a very sad past. Some people have had to suffer atrociously from it. Her agitation appears sometimes also at night, her physical condition is not bad, but her mind is very feeble. She does not seem to suffer from not having any visits, she lives in a dream and fortunately does not miss her beloved ones.”

Perla clearly suffered from traumatic wartime memories. Today therapists might be able to better treat what I can only assume was some form of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder potentially along with dementia as she aged, but even now these can be very difficult to manage, much less treat effectively. There was probably little her caretakers could do to help ease her mental trauma. She simply did what others in her generation and situation had to do; she endured. On May 6, 1971, at 10 o’clock in the morning, she died. Chateau De Villeniard informed Grandpa George that in the end Perla was quite senile and traumatized by the events of the war, and that she suffered. They wrote, “I think her physical and mental state was much degraded, since she could not eat alone, nor could she dress herself; she was even incontinent, and one could only wish the delivery of this poor human being, who has suffered so much.”

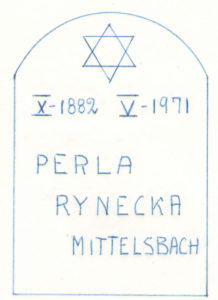

Grandpa George felt incredible guilt at not being by his mother’s side in her final days. In the letters he wrote to Chateau De Villeniard after her death he was very concerned with making sure she received a proper burial and that a tombstone mark her grave. He was assured she was properly buried in the Vaux S/Lunain cemetery. Grandpa George designed the tombstone himself. Someday I hope to journey to Le Mans to visit her grave to pay my respects.

Grandpa George’s sketch. Mittelsbach was her maiden name. Rynecka is the Polish feminine form of Rynecki