Stephen Applebaum of The Jewish Chronicle:

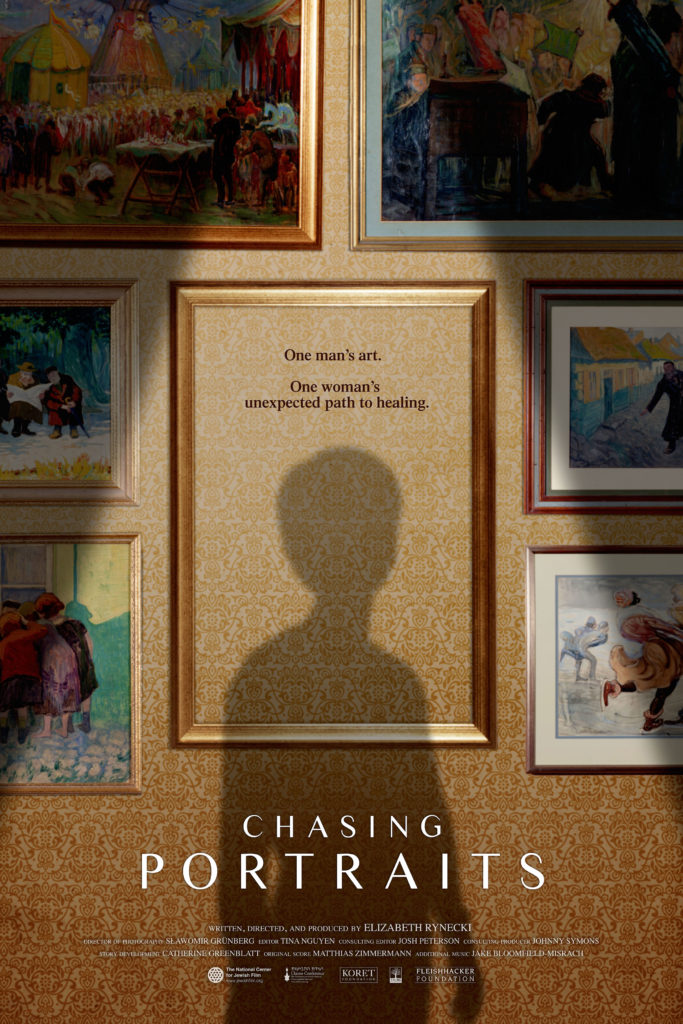

Searching for her great-grandfather’s lost pictures

Elizabeth Rynecki’s new film tells the story of her quest to find her great-grandfather’s works of art which captured the world of pre-war Polish Jewry

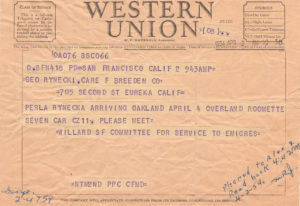

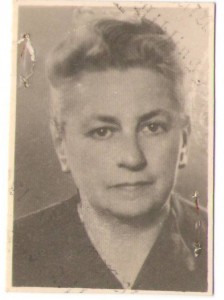

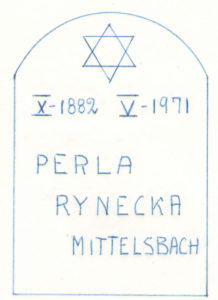

Elizabeth Rynecki grew up in San Francisco in the 1970s, surrounded by paintings by her Polish great-grandfather, Moshe Rynecki. These artefacts from a life snuffed out in the Majdanek extermination camp, haunting and evocative depictions of Jewish life, were surviving expressions of the artist’s love for the community in which he was raised, and which was swept away violently after 1939.

Almost uniquely, Moshe’s work offered visual impressions of a world that was already changing before the outbreak of war, making them historically and socially significant, and different from the work of survivors who painted suggests Elizabeth over the phone from her home in America.