Included in the Otto Schneid archive at the University of Toronto’s Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library are several newspaper clippings with information about some exhibitions that included Moshe Rynecki’s work. This article, written in German, was particularly difficult to read because of the use of the font, Fraktur. I eventually was able to transcribe the text which I then put through Google Translate. The results (included in this blog post down a bit further) are not brilliant, but they give you a sense of the content of the article. I am hoping that someone who speaks German might take a look at this and help me refine the translation.

Included in the Otto Schneid archive at the University of Toronto’s Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library are several newspaper clippings with information about some exhibitions that included Moshe Rynecki’s work. This article, written in German, was particularly difficult to read because of the use of the font, Fraktur. I eventually was able to transcribe the text which I then put through Google Translate. The results (included in this blog post down a bit further) are not brilliant, but they give you a sense of the content of the article. I am hoping that someone who speaks German might take a look at this and help me refine the translation.

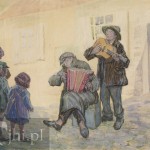

I find a few things about this article compelling and eye opening. The first is that my great-grandfather was so prominently featured in this newspaper (whose title I do not know). The second is that all four of his paintings included in this article have titles, which lends quite a bit of history and insight to my great-grandfather’s way of thinking about his paintings. [Read more…]