After Paris’ liberation from the Nazi occupation, a German soldier’s photo album containing pictures related to the Möbel-Aktion” campaign was found. The M-Action campaign, or furniture action campaign, was one in which the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) looted approximately 70,000 homes of French, Belgian, and Dutch Jews who had either fled or had been deported. The stolen items were then inventoried, photographed, and eventually transported to Germany. Alfred Rosenberg, the Reich Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories, wanted the items to furnish German administrative offices in the East.

After Paris’ liberation from the Nazi occupation, a German soldier’s photo album containing pictures related to the Möbel-Aktion” campaign was found. The M-Action campaign, or furniture action campaign, was one in which the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) looted approximately 70,000 homes of French, Belgian, and Dutch Jews who had either fled or had been deported. The stolen items were then inventoried, photographed, and eventually transported to Germany. Alfred Rosenberg, the Reich Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories, wanted the items to furnish German administrative offices in the East.

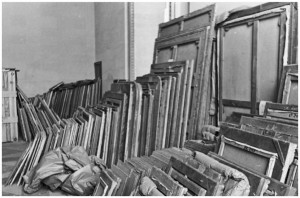

A Parisian department store, Lévitan, served as an interim storage space before the looted goods were transported to Germany. When the stolen items arrived at the department store, Jewish internees assigned to this work opened crates and divided the contents into “departments” in order to display the goods with other similar items. Some of the images in the album show the stolen goods arranged into shop-like displays, presumably for the benefit of high-ranking Nazi officials whose visits are depicted in some photos. It is one thing to know this historical fact, it is quite another to see these photographs. In these images we see furniture and crates loaded onto trucks, and images of everyday household objects – pots and pans, dinner sets, children’s toys, musical instruments, bedding and linens, and stacks of empty frames – sorted, stacked, and disconnected from their true owners. We are, as author Sara Gensburger states in her title, Witnessing the Robbing of the Jews.

We know the Nazis took everything – people, communities, lives, homes, land, and personal property – but these photographs show the massive extent of the looting. And more than anything else,

We know the Nazis took everything – people, communities, lives, homes, land, and personal property – but these photographs show the massive extent of the looting. And more than anything else,  these photos speak volumes about the attempts to erase and forget the people and families whose stories are behind each and every one of these items on display. Nazis were invited to buy these goods, and they did. But as we gaze upon these photos we bring with us an understanding of what these items without their owners really means. The snapshots of personal property becomes incredibly surreal and deeply disturbing because although we don’t know the exact fate of each of the people who once owned these goods, we have a pretty darn good idea of what happened to them.

these photos speak volumes about the attempts to erase and forget the people and families whose stories are behind each and every one of these items on display. Nazis were invited to buy these goods, and they did. But as we gaze upon these photos we bring with us an understanding of what these items without their owners really means. The snapshots of personal property becomes incredibly surreal and deeply disturbing because although we don’t know the exact fate of each of the people who once owned these goods, we have a pretty darn good idea of what happened to them.