My journey, as well as my relationship to the work of my great grandfather, has followed a complicated and winding path. Perhaps it is best described as a journey of many steps. I first became interested in the story after the death of my grandfather in 1992. While the memoir he left in the trunk of his car kindled a strong interest in my father’s and grandparents’ stories of survival, I was put off by my father and grandmother’s reticence to talk about the War years and my fear that questions would inflict too much pain on their psyche. In part because I was frustrated in my desire for more details, I developed a broader interest in understanding the impact of the Holocaust on the “Second Generation,” the children of survivors. The book, Children of the Holocaust: Conversations with Sons and Daughters of Survivors by Helen Epstein had a large impact on me. Epstein, the daughter of Holocaust survivors, whose “secret quest,” was to “find a group of people who, like me, were possessed by a history they had never lived. I wanted to ask them questions, so that I could reach the most elusive part of myself” made a lot of sense to me and had a powerful impact on me. I had never met other children of survivors and the idea that we might share a similar background and understanding of the Holocaust was compelling.

Shortly after reading Epstein’s book, I was introduced to the Maus books by Art Spiegelman. This was a seminal event for me. The two books that make up the series are biographic graphic novels about the Spiegelman family’s pre-war life and story of Holocaust loss and survival told from the perspective of the son of survivors.

I vividly remember the night I read the book. I was in my apartment in Davis, California. I lived by myself. It was early in the evening, but it was quickly getting dark. I became frightened and disturbed. A guy in my Master’s program I liked (who many years later became my husband) called me out of the blue to talk. I started crying. He didn’t know me well enough to come visit me in my apartment. He suggested I go to school. He said he’d meet me there and keep me company. What had moved me to tears and so frightened me were the visuals and approach of the book. Art Spiegelman articulated and presented the second generation in a way that made me feel that I wasn’t alone in trying to figure out how to live in the shadow of the Holocaust. Perhaps the most powerful and haunting image for me is the one that appears in Maus II: And Here My Troubles Began on page 41. I wrote about this single page, titled, “Time Flies,” in my Master’s thesis:

“Time Flies” consists of five frames that show Artie sitting at his drawing table. The first two frames show close-up profiles of Artie. In these frames we see that Artie is human, but that he is wearing a mouse mask. The third frame moves back from the drawing table and displays the entire drawing table and Artie’s upper torso. Again, in this frame we observe Artie’s profile. In the fourth frame Artie turns toward the reader. Although he still has the mouse mask on, we no longer see the ties at the back of his head. In the final frame Artie sits hunched over his desk. Under the desk we see a pile of mice corpses and outside his window looms a concentration camp guard tower.

I found the image vivid and disturbing. It was troubling not just because of the dead mice bodies, the flies hovering above, and Spiegelman’s success as an author/illustrator sitting above the death and destruction, but because Spiegelman articulated very graphically a sentiment that resonated with me; he visually explored and explained the tension between wanting to hold true to survivors’ stories and needing to address his own, once removed, relationship to the Holocaust.

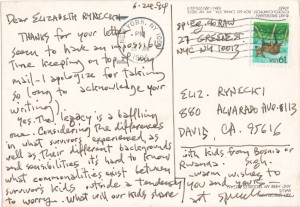

I wrote to Art Spiegelman, telling him his story spoke to me on a very personal level and explaining he’d had a profound impact on me. I never thought he’d actually write back, but he did. It was thrilling to get a postcard  from a Pulitzer Prize winning author, but getting the postcard was so much more than merely a brush with fame. Art Spiegelman and I, even though we’d never met, shared an experience – we were both children of Holocaust survivors and we were both struggling to figure out what that meant and what we should do about the legacy. His pronouncement that the “legacy is a baffling one,” rang true for me. Yet I felt comforted knowing I was not alone in my confusion about how I could respect survivor’s stories while still acknowledging my own experiences. If Spiegelman didn’t know what to make of the legacy (and he’d written two books about trying to understand how he fit into his father’s story) then I didn’t have to have all the answers either. It really was a tremendous relief and one that allowed me to move forward and explore my own issues without feeling guilty about doing so.

from a Pulitzer Prize winning author, but getting the postcard was so much more than merely a brush with fame. Art Spiegelman and I, even though we’d never met, shared an experience – we were both children of Holocaust survivors and we were both struggling to figure out what that meant and what we should do about the legacy. His pronouncement that the “legacy is a baffling one,” rang true for me. Yet I felt comforted knowing I was not alone in my confusion about how I could respect survivor’s stories while still acknowledging my own experiences. If Spiegelman didn’t know what to make of the legacy (and he’d written two books about trying to understand how he fit into his father’s story) then I didn’t have to have all the answers either. It really was a tremendous relief and one that allowed me to move forward and explore my own issues without feeling guilty about doing so.