Guest blog from Catherine Greenblatt. May 11, 2015

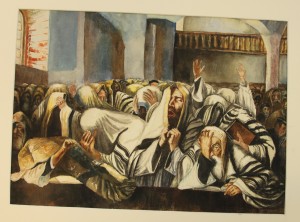

Yesterday, Elizabeth, Slawomir, and I did research at the Jewish Historical Institute (ZIH) in Warsaw to follow up on a few things that we missed last October, when for two full days we set up shop in the offices of the curators there. When we were first there, in the excitement of looking at 52 paintings in one place and at one time–we somehow missed the 52nd painting. We saw it yesterday. (Thank you Jakub and Michal for finding the elusive piece.) And we had quite an interesting experience viewing it. It is called “Prayer: Day of Atonement,” and at first glance, Elizabeth and I questioned whether or not the piece was in fact a Rynecki at all. Its lines are sharper than a typical Rynecki watercolor, which is typically composed of broad strokes that overlap and create darker zones of overlay. Also, the light is quite a bit starker and floods entire fields of the painting. And most striking, some of the faces are rendered in a more realistic style, with discernible features and definition, whereas Rynecki typically favors broad movement and gesture over precise figuration. The overall composition is familiar, however, as there is a lot of activity in all areas of the pictures, and the sense of gesture is strong. Areas of watercolor resemble Moshe’s typical style, which is more expressionistic. But as we looked and looked, the less certain we became that the piece was in fact Moshe’s.

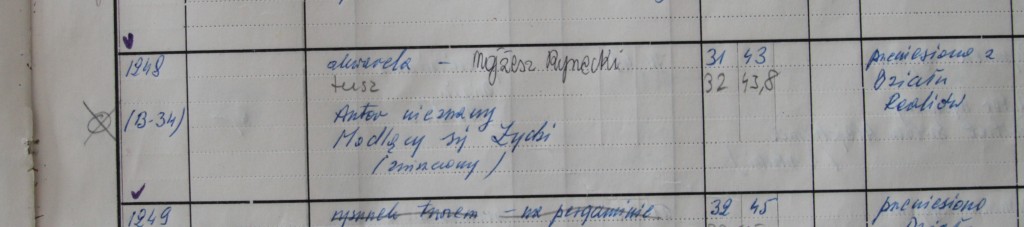

Clues came later in the morning, as we looked at the intake ledger. (A gigantic book with handwritten entries for each and every piece in the archive, a bibliophile’s vision straight out of the 19th century, detailing the price paid for the piece, the dimensions of the piece and its condition on arrival, the subject matter and title, the medium or materials, its projected value, and so on). Interestingly enough, the first curator to write notes about the piece ascribed it to no painter in particular—“author unknown”—but later a second ZIH curator ascribed it to Rynecki. So we weren’t the only ones pondering the question of authorship, including Alex Rynecki, Elizabeth’s Dad, who viewed a digital image of the piece as well. Moreover, the painting had recently been restored, which sharpens its lines, clarifies its spaces, heightens its color. As a result the accumulation of these sometimes subtle effects can be a dramatic change in mood and meaning.

In addition to the intake ledger, ZIH also keeps information cards with black and white photos of the piece attached. Elizabeth photographed each and every one of the inventory cards, which also tell the year ZIH acquired any given piece and what is known of its previous owners and the exchange that took place. When we last visited in October, these cards were not accessible, due to a major renovation of the building. So today we learned something that we didn’t know: that a majority of the pieces were sold by two individuals, one P. Goldberg of Warsaw in 1946 and one Jan Zobrowicz of Wloch, near Warsaw, in 1964. Chasing Portraits thrives on these kinds of tantalizing leads, which we hope will help us locate more paintings and reveal more stories of how this work has survived.