[NOTE: Today’s post is written by Catherine Greenblatt. Cathy is part of the Chasing Portraits documentary film production team.]

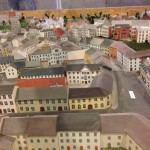

One bone-chilling, digit-numbing afternoon in Lublin, after visiting the concentration camp Majdanek, an experience I’ve yet to metabolize, we visited The “Grodzka Gate – NN Theater” Center. Grodzka Gate – NN Theater occupies a building that is a literal bridge between what once was the Jewish and what is still the Gentile quarters of the town, where different cultures and religions could meet and pass into one another’s neighborhoods. Architecture becomes metaphor in Grodzka Gate, as the organization fully embraces the actual and figurative space of the bridge. The Jewish part of the city is now completely gone, the streets that once were busy with commerce and life are now silent, paved over, their vitality slipping away from the collective memory of Lublin. It is difficult to categorize simply the work that “Grodzka Gate – NN Theater” does. It researches, explores, documents, and makes present again the lives of people who before the war made up one third of the town’s inhabitants. Their alchemy is part urban archaeology, part performance art, part gallery installation, part photographic archive, all filtered through the medium of public education and civic engagement. All of these gestures and research are then communicated through the ethical imperative of communal mourning and memory. Through photographs, maps, civic records, and other historical documents, “Grodzka Gate – NN Theater” finds remnants of lost lives and then animates them with conversation, live performance, and storytelling. Learning about this intelligent, heartfelt work warmed us as much as the hot milled wine and mushroom soup we had eaten earlier for lunch at a nearby traditional Polish restaurant.

One bone-chilling, digit-numbing afternoon in Lublin, after visiting the concentration camp Majdanek, an experience I’ve yet to metabolize, we visited The “Grodzka Gate – NN Theater” Center. Grodzka Gate – NN Theater occupies a building that is a literal bridge between what once was the Jewish and what is still the Gentile quarters of the town, where different cultures and religions could meet and pass into one another’s neighborhoods. Architecture becomes metaphor in Grodzka Gate, as the organization fully embraces the actual and figurative space of the bridge. The Jewish part of the city is now completely gone, the streets that once were busy with commerce and life are now silent, paved over, their vitality slipping away from the collective memory of Lublin. It is difficult to categorize simply the work that “Grodzka Gate – NN Theater” does. It researches, explores, documents, and makes present again the lives of people who before the war made up one third of the town’s inhabitants. Their alchemy is part urban archaeology, part performance art, part gallery installation, part photographic archive, all filtered through the medium of public education and civic engagement. All of these gestures and research are then communicated through the ethical imperative of communal mourning and memory. Through photographs, maps, civic records, and other historical documents, “Grodzka Gate – NN Theater” finds remnants of lost lives and then animates them with conversation, live performance, and storytelling. Learning about this intelligent, heartfelt work warmed us as much as the hot milled wine and mushroom soup we had eaten earlier for lunch at a nearby traditional Polish restaurant.

Grodzka Gate began as a theater company, and though its mission took a turn when it fully realized the meaning of its location, there is no doubt that its work continues in a performative vein. In one civic performance, the stories of survivors commingle with those “righteous” Poles who rescued or hid Jews, each of the storytellers forming a line on each side of the Grodzka Gate, each one becoming witness for the other. As each person spoke, a lit candle would pass between each individual all along the line, and a handful of earth would be collected. Into each pile of earth a plant would be planted, a sign of life in a city that lost too many. I have long been fascinated by the speech of ghosts and have trained my ears to hear what it is they have to say. Poland is overwhelmed by ghosts, the airwaves are choked by their broadcasts, and not all of them are speaking in Yiddish. In the West, we don’t really learn about the suffering of Poles during the war, especially under Soviet occupation. The example of Grodzka Gate gives us an ethos of compassion and empathy and, above all, a desire to know what all of us are missing.