“I realize how much I care about how this hard and soft, losable object has survived. I need to find a way of unraveling its story. Owning this netsuke – inheriting them all – means I have been handed a responsibility to them and to the people who have owned them. I am unclear and discomfited about where the parameters of this responsibility might lie.”

– Edmud de Waal

The Hare with Amber Eyes by Edmund de Waal, a world-famous ceramicist, is a memoir about his inheritance of 264 tiny Japanese wood and ivory carvings (netsuke) and his desire to know who has held them and how the collection managed to survive the Second World War. This passage from his book speaks to me in so many ways. I understand what it’s like to inherit art, I know the desire of wanting to unravel the story, and I completely relate to feeling baffled about what the meaning and shape of this responsibility has in my own life.

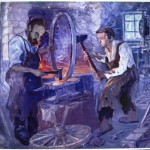

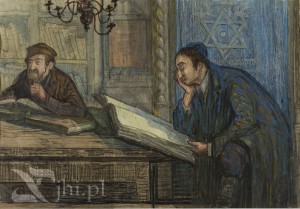

Today’s photograph is one of the 17 by Moshe Rynecki emailed to me by the Jewish Historical Institute (ZIH) several weeks ago. ZIH has titled the piece, “Stolarz zydowski,” which I believe translates to: Jewish Carpenter. It is undated.