On Monday Chasing Portraits was named Indiewire’s Project of the Day. Today is the run off to determine the Project of the Week!

Please vote for Chasing Portraits to help it win! (Yes, this link will take you to the voting page!)

The weekly prize is a digital distribution consultation with SnagFilms, and the Project of the Month winner (to be decided later) will receive a creative consultation with the Tribeca Film Institute and will become eligible for Project of the Year. And, of course, it’s GREAT publicity for the project.

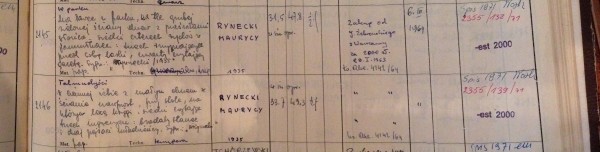

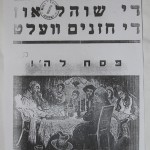

For the last 9 days, we have been visiting many sites in Poland that each play some part in piecing together the puzzle of Moshe Rynecki’s life and work. We have relied upon the

For the last 9 days, we have been visiting many sites in Poland that each play some part in piecing together the puzzle of Moshe Rynecki’s life and work. We have relied upon the