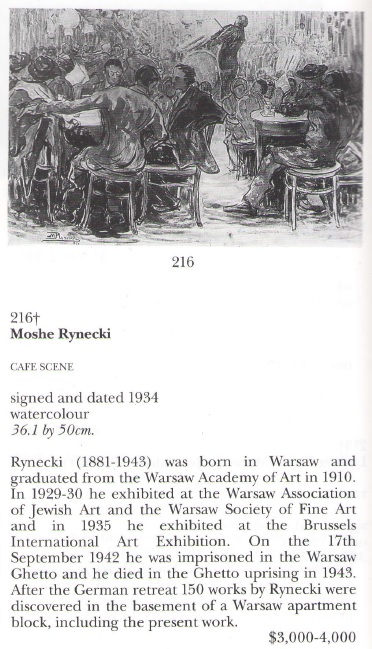

My favorite sorts of emails? The ones with the lovely and unexpected gift of the find of a Rynecki painting I’ve never seen. Yesterday I got an email from my Polish provenance research friend, Yagna Yass Alston, with a photo from a 1993 Sotheby’s Tel Aviv auction catalog. The photo shows a painting, a Cafe Scene.

My favorite sorts of emails? The ones with the lovely and unexpected gift of the find of a Rynecki painting I’ve never seen. Yesterday I got an email from my Polish provenance research friend, Yagna Yass Alston, with a photo from a 1993 Sotheby’s Tel Aviv auction catalog. The photo shows a painting, a Cafe Scene. This photo is not great, and I’ve now ordered a copy of the catalog (it’s amazing what you can find online!) so I should have a better image in a few days. The page from the auction catalog shows the painting and provides a brief biography. But the incredibly fascinating bit (yes, above and beyond seeing a new image!)? It says…”after the German retreat, 150 works by Rynecki were discovered in the basement of a Warsaw apartment block, including the present work.” This is NOT a piece put up for auction from my family. So does this mean that whoever sold this piece has 149 others?! If so, who is this person? Where do they live? How do I find out more about what else they’ve got? And who owns this piece today? And do THEY have any others? So many questions. Like I always say, it’s why the documentary film is titled, Chasing Portraits.

[note: post updated 20 January 2015 with higher quality images from the auction catalog.]

I really, really, wish I could explain what it’s like to get an email that says, “I’m sending you images and links….have you seen these images?” There’s palpable excitement in the moment before I get to actually see the image – my heart

I really, really, wish I could explain what it’s like to get an email that says, “I’m sending you images and links….have you seen these images?” There’s palpable excitement in the moment before I get to actually see the image – my heart