[Note: I originally posted this on my blog in March 2012. In June 2014 I posted it in a Huffington Post blog with the title, “The Art of Moshe Rynecki,” along with a slideshow of several Moshe Rynecki paintings.]

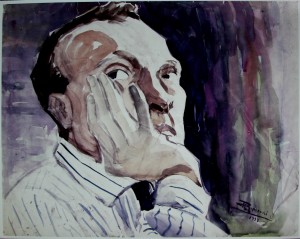

The category of Jewish Art History cannot be simply subsumed into a generalized European art history. The modern artist as the author-agent of the work of art is a relatively new persona and figure for Jews, emerging only in the nineteenth century along with greater historical movements of emancipation for Jews in Europe. My great-grandfather was split between affinities: on the one hand, he was a painter of traditional Jewish life in Poland, settling his gaze upon scenes of synagogue, teaching, labor, and leisure. In this, his paintings are an invaluable source of visual information about a world that has vanished. On the other hand, his self-portraits reveal a man apart from the world he depicted, a modern subject rendered in a minimalist style with expressionist lines in contemporary and not traditional dress. The tension between the ethnographic content of the painting and the modern gesture of the cosmopolitan painter is a fascinating one, a tension that plays itself out as Jews became modern citizens of European capital cities (one thinks of Freud as Moshe’s contemporary). At the same time, the shtetl lay just over the border, where the ostjuden, Jews of the east, with their foreign, traditional, anti-modern culture, lived.

This tension, and the duality which gives rise to it, is even greater than it might seem, because the very idea of talking about Jewish artists was once unfathomable. The Jewish community’s strict interpretation of the Second Commandment’s prohibition against graven images would not allow for Jews to be artists. Today the concept of a “Jewish painter” is less contradictory and much more accepted. Pioneering artists in the nineteenth century such as Moritz Oppenheim, Camille Pissarro, Maurycy Gottlieb, and Max Liebermann were forced to make difficult choices about whether to embrace their religious background and incorporate it into their work, or instead to elide their ethnic heritage. Their individual choices ultimately made it easier for artists who followed in their footsteps to navigate and live in a broader society without abandoning their Jewish roots.

In fact, for some painters, art emerged directly from their Jewish identity; there was no separation between their Jewish identity and their art. For others, political freedom made it possible to relinquish the Jewish world and to expand their opportunities and experiences. For a third group, there was a constant struggle to find a balance between the demands of the contemporary art world with their own religious background. Those who navigated this path seemed to live in two worlds; they were motivated to accurately depict religious study and rituals, but did not want to paint classically religious paintings. Instead of attempting to document a devout lifestyle, these artists sought to accurately reflect the Jewish experience in its historical context, and to celebrate the people and their traditions without making their works overly brooding or nostalgic. These works appealed to the growing acculturated middle class Jews living in Central and Western Europe. The art reflected the middle class’ struggle to live a contemporary life while searching for ways in which to preserve their Jewish identity. The paintings helped them to do both.

My great-grandfather’s dual identity as a Jew, and as a member of the growing middle class in the more secular setting of Warsaw, allowed him to intimately paint aspects of Jewish life and tradition and yet to distance himself to position himself as a witness, an ethnographer of the community. It is this philosophy and approach that convinced him to go into the Warsaw Ghetto to, “be with my people” and to paint and record the tyranny and cruelty perpetuated by the Nazi regime. Ultimately this decision cost him his life.

Elizabeth, you’re doing a wonderful job, trying to recapture as much as you can, not only the story but also your great-grandfather’s art, he would’ve been proud of you.

Johanna, Holocaust survivor/author

http://www.johannareiss.com

I am so pleased to visit your updated (and fascinating) website! Yasher Koach to you and other members of your family for this ongoing quest. I wish you great success in your endeavor.

You may be interested to visit the Jewish Art Education website (www.jarted.org) and note particularly the ongoing blog. Currently, there is a post by Ori Soltes, Ph.D. about “What Makes Jewish Art Jewish?” JAE anticipates many upcoming posts from contemporary Jewish artists about the Jewish influence in their work. I think you will find them of great relevance.

JAE also creates CDs and DVDs (perhaps we could make one of Moshe Rynecki’s work????) that are used for JAE presentations and in various educational sites. Please contact me at: teck.jarted@gmail.org if you would like to pursue this idea. Again, my Congratulations to you on what you have already accomplished!

Best,

Myrna Teck, Ph.D.